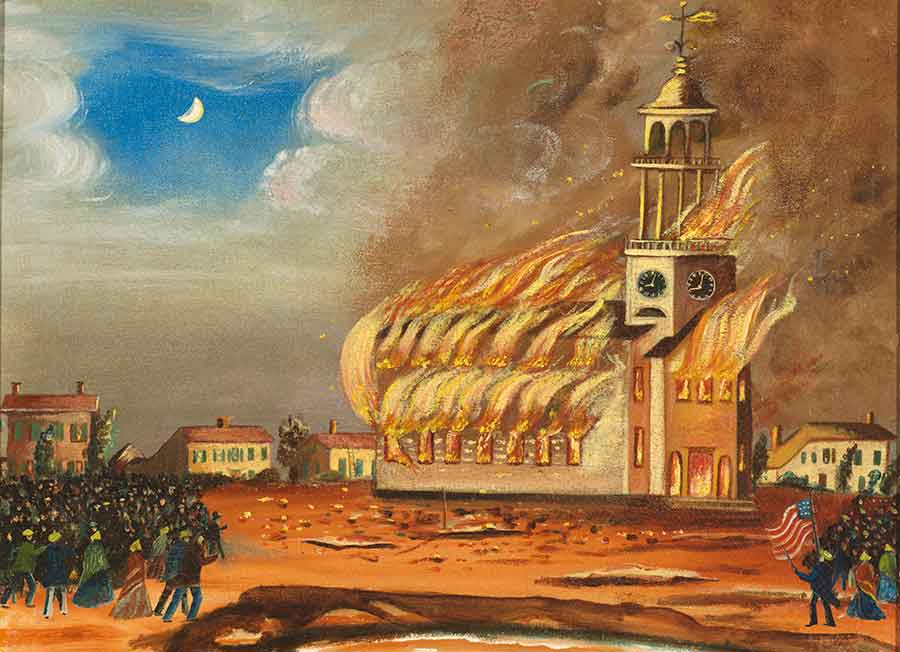

John Hilling, The Burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, ca. 1854, oil on canvas, 21 1/2 x 27 3/8 x 2 1/8 in. (54.6 x 69.5 x 5.4 cm.). Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Creative Commons

When (and Why) did the Good News become BAD news?

I don’t think too many people would argue with me when I would say that our world is a very angry and turbulent place right now. There are a lot of pressing, urgent, and important issues dominating the headlines just as much as there is frivolous click-bait that consumes way more of our time, stress, and energy than it ought to. The truth, it seems, is becoming further and further removed from reality, and more and more entrenched in subjective experiences. From issues like the Russia-Ukraine conflict, to increasing suspicion towards China, to Climate-change crises, to social justice issues like Black Lives Matter, Every Child Matters, and LGBT+ inclusion, and everything in between, there is seemingly an unending supply of things to worry about, get angry about, or to become an activist about in some way, shape, or form.

Below the surface of all of this is an important theme: things are not the way they’re supposed to be. Whether or not we agree on what “supposed to be” actually means, there is a universally-agreed-upon position (if we’re willing to admit it) that the world – and subsequently our lives – are not optimal. Something is inherently wrong.

From a non-biblical perspective, that ‘something’ is in ways far more ambiguous to define, just as much as its proposed solutions are varied and at times contradictory. If I were to observe an underlying trend and thread in all of the differing definitions of “what is wrong with the world” outside a Christian context it would be this: “we have inherited a world that is broken; it is our job to fix it; but it is so far gone that we need to completely tear it down and start all over”. The fancy, philosophical word for this is “deconstruction”: we must “deconstruct” what is in order to “re-construct” what ought to be.

And it certainly is appealing, because we all know human nature – we are notoriously stubborn creatures of habit who do not easily change. This becomes all-the-more apparent when there are many of us thinking and moving the same way – ideas, practices, and systems become entrenched because so many people buy into them. The only way, it seems, to change those ideas and practices is to completely tear them down and replace them with something else. What that ‘something’ is cannot always easily be defined, only in that it obviously cannot be the same as what already is. In some ways, where things get pushed is “anything but what we already have”. The most obvious target of such deconstructionism is our institutions. As institutions by their very nature are concrete expressions of group ‘policy’ and ‘practice’, so they are at the very core of what ought to be deconstructed in favour of that ‘something’ we cannot clearly define. This is not leaving the church unscathed.

This deconstructive thinking has been around (especially mainline) churches for quite some time. As congregants have consistently observed a decline in membership and participation, so a corresponding anxiety begins to rear up, sounding the alarm bells that something needs to change. Unfortunately, instead of properly taking the time to discern and diagnose why people are disengaging or leaving the church (sometimes leaving for other churches, sometimes leaving the church altogether), our anxiety encourages us to magnify what we perceive to be wrong with the church as we start searching for solutions to fix it. All we can really say with confidence is that what we have been doing is not keeping people in [our] church, nor is it bringing new people into it. But this leads us to conclude that the problem is with the institution: the church itself (or at least “our church”). This may be partly true, but it is not the whole truth. Many of us have been around the church long enough to know that it seems no matter what we change – in theology or practice – our churches are, on the whole, shrinking and not growing. This can lead to disillusionment, frustration, negativity, and infighting, along with louder calls to “tear it all down”, because clearly the system isn’t working. But is the problem (if indeed it is a problem) really with the institution of the church? Perhaps the ‘problem’ is actually with people.

The issue we’re confronted with, however, if we call this a people problem as opposed to an institutional problem, is that you can’t deconstruct people. That ‘something’ that is wrong with the world that makes it less-than-ideal at best, and totally depraved at worst, from a biblical perspective is that people are sinful. The problem with the world is not its institutions, but the people who comprise them, because they are sinful. Totally depraved really captures it.

If history has taught us anything, is that every system or structure that is set up to replace a previous ‘inadequate’ one is inevitably replaced with something else later on because of inherent problems with the solution. Another way of putting it, as is often said, “the only thing we learn from history is that we don’t learn from history”. If we look around us at the world today, we are repeating many of the same mistakes our ancestors did. The underlying cause is not that we are ignorant or arrogant (although these certainly factor in), but because of the simple reality that we are sinful human beings. We are not perfect. We are selfish and self-centred most, if not all, of the time. We lie, we cheat, we steal, we complain; we hurt one another, criticize one another, look down on one another, bully each other, and undermine each other. If the ‘something’ that needs to be fixed in the world is sinful people and not the institutions they have created, then that is a problem too great for any human being to solve. The institutions are the easy targets – the low-hanging fruit – the things we hope that if we can just change the institutions, then the people will follow. Only, not all people follow all of the time; there are always rebels – and the institutional apple-cart is repeatedly upset. So how, then, do we deal with the people problem?

The reason I entitled this post the way I did is because I’m trying to help us wrestle with the question of how the church, the place where THE Good News is proclaimed and experienced, has become a place of bad news in that it has become the brunt of so much criticism and anger, and a place often filled with negativity. How is it that the church has transformed from a refuge for the broken and hurting to a hotbed of conflict and controversy over sometimes the most inane and mundane of things? If a solution is to be found, it is not necessarily going to be found in destroying or reforming the institution, but in reforming the people who comprise it.

As I mention above, if the ‘something’ that needs to be fixed in the world is sinful people and not the institutions they have created, then that is a problem too great for any human being to solve. But it is not too difficult for God to solve. In fact, He’s already done it, and continues to do it each and every single day. Jesus dealt with our sin on the cross. Jesus’ death and resurrection makes possible a new way of thinking and being in the world. The GOOD NEWS of the Gospel of Jesus Christ is that people can be and are made new in Him. This doesn’t mean that we are perfect, but it does mean that there is grace and forgiveness when we do screw up, and that God gives us everything we need through the Holy Spirit to do differently next time. The church is a place we go to be reminded of this fundamental truth: we are sinners saved and transformed by God’s grace. Knowing and understanding this is the only way to deal with the sin problem in the world, and the sinful institutions it has created.

So, before we start thinking about or talking about “deconstructing” the church, let’s perhaps get back to seeing things, and people, as they really are. Instead of trying to make the church something (or anything) other than what it is, maybe we can start trying to bring it back to what it ought to be from a biblical perspective: a place where sinful human beings go to be transformed by God’s grace by encountering Him through Scripture, prayer, and song, and perhaps most importantly, through our relationships with one another.

In line with what we talked about this past Sunday morning about bearing grudges and judging one another, I have a small frame in my office windowsill with a quote in it: “Be the change you wish to see in the world”. Rather than externalizing everything and talking about everything that is ‘wrong’ out there, we need to take a deep look into ourselves and start with what is ‘wrong’ in us, and allow God to deal with that first. I think we will be surprised if our relationships to one another don’t begin to change when we stop blaming and getting angry at each other for problems in the church and in the world, and start taking responsibility for the part we have to play in that.

Recent Comments